“We had John Fashanu in here last week. You could hear that flash c*nt ‘Awooga’ from the other side of the car park.”

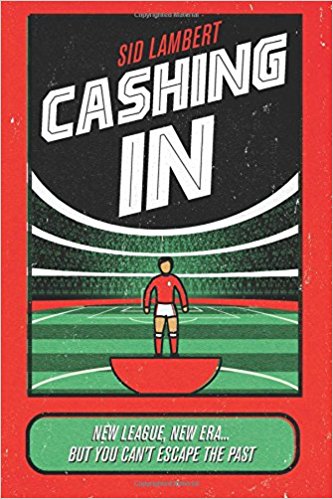

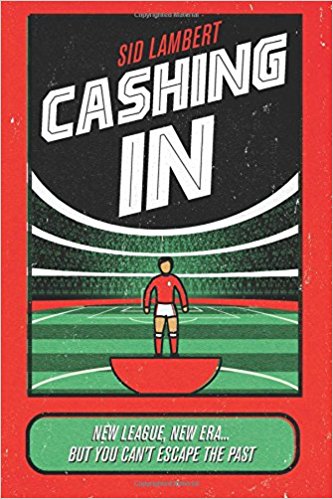

Cashing In is the new 90s football novel by Sid Lambert set in the inaugural Premier League season. It tells the story of Ray Cash, a 19-year-old footballer disillusioned with the game after a tragic accident involving his twin brother. Pressured into pursuing his career by his grieving dad, he signs with larger-than-life agent Paul Francisco. In part one of our serialisation, Ray meets his new representative for the first time.

The way to sign with Francisco

“HERE HE IS. ENGLAND’S NEW NUMBER SEVEN!!!”

The hoarse northern voice bellowed across the empty parking lot. We were on a miserable industrial estate fifteen minutes outside of Manchester. In front of us stood a decrepit red brick building that could have passed for an old laundry house were it not for the gawdy neon sign above the door:

FFS: FRANCISCO’S FOOTBALL STARS

“Come on in, son. We’ve been waiting for you.”

Paul Francisco strode towards us. He was six feet tall, weighing in at roughly eighteen stone and built like a rugby prop. In fact, with his slicked-back brown hair and imposing moustache he could have passed as Bill Beaumont’s stunt double, were it not for his extraordinarily bronze skin and equally impressive jewellery collection. Every finger was adorned with gold whilst a watch the size of a medieval sundial nestled cosily on his ample left wrist.

His huge paws swallowed mine as we exchanged a sweaty handshake.

“Great to meet you, Cashy,” he said. “My brother’s told me all about you. Don’t you worry, son. You’re in safe hands here.”

Paul shook hands hurriedly with Dad, who looked dumbfounded by the sight before him. This wasn’t quite the picture either of us had imagined. Undeterred, Paul ushered us into his place of work.

“You’re a lot taller than I thought you were. That’s good. Managers like a bit of height – useful at set pieces,” he winked. “Fuck me, you’re a skinny bastard though. I don’t know whether to open the door or post you through the letterbox.”

He roared with laughter and motioned Dad and I inside.

“Welcome to Francisco’s Football Stars,” he said. “You reach for the stars and I’ll drag ‘em down for you. That’s the way we do things here.”

Awooga

If the outside looked unremarkable, there was at least plenty to remember about the interior of Paul’s office. The door led into a compact space with an empty reception desk and a cheap sofa and coffee table outside the door to what was obviously Paul’s private office. Huge framed pictures of footballers past and present graced every wall, each image suitably defaced with a hasty scrawl from the star in question.

“Look at those names eh, Cashy,” he said. “Brian Kilcline, John Sheridan, Brian Deane, Ian Crook, Rod Wallace. First Division royalty that lot.

You’ll be up there too, son. Don’t you worry.”

He patted me on the shoulder and I nearly crumpled under the force.

“And here’s my pride and joy…”

He pointed over to the wall behind us near the door, where the whole surface area was occupied by a life-size picture of Paul and Newcastle United striker Micky Quinn. Both men were clutching a hot dog and a can of lager against the backdrop of an overcast racecourse.

“What a day that was. Me and Quinny celebrating his new contract,” he said. “We’ve got him down to 10% body fat, you know. It’s the 90% Heineken that’s the fucking problem.”

His hearty laugh nearly shook the foundations of the building and it continued as he led us into his private office. Unlike the rest of the building it was an immaculate space and free from football paraphernalia. The desk looked like it was made of solid oak and regularly varnished. It was adorned with a lamp, a phone and a clumsy assortment of files strewn across the remaining surface area – the epitome of organised chaos.

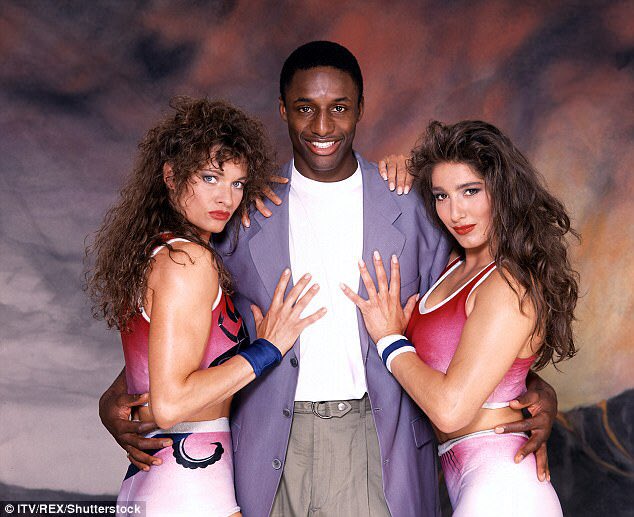

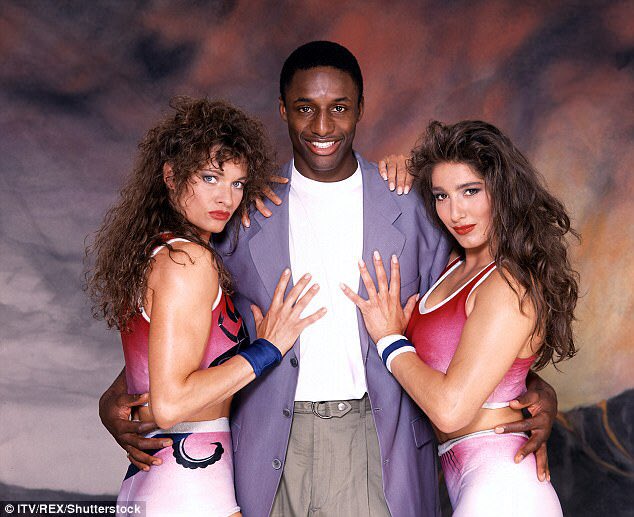

(Image: ITV/Rex Shutterstock)

The walls were a faint beige, contrasting with the warm red carpet, and behind Paul’s desk was an image I recognised from my history textbooks at school. It was from World War Two, depicting the view from inside one of the warships as the troops unloaded onto the French beaches into a barrage of German machine gun fire. On the bookshelves to the right, there were numerous tomes on war and a couple of Winston Churchill biographies.

Aside from two dark grey filing cabinets, that was the sum total of decoration, except for one curiosity in the corner of the room. There stood a large shoe rack, immaculately maintained in stark contrast to the anarchy of the desk space. It held maybe twenty pairs of shoes, mainly black and deep browns. They were all in pristine condition. Next to the shoe rack was an array of materials – buffers, brushes and polish - charged with keeping them that way.

Paul shouted out to his secretary to bring in refreshments. She tottered in immediately, struggling to remain upright. At first I thought it might be the shoes that were causing her unbalance but as my eyes drifted upwards I could see that in fact it was the astonishing size of her chest, barely sustained by her implausibly small vest top.

“Teas all round?” she asked.

Dad and I nodded, both awestruck by the freak of nature before our eyes. With long blonde hair big blue eyes, and make-up that most Page Three girls would be proud of, it was tempting to assume that the recruitment policy for secretaries at Francisco’s Football Stars might not be based on words per minute.

“How many sugars do you want today, Paul? Five or six?” she asked.

“Fuck it. Let’s go for seven eh, Christine. I’ve got England’s next right winger in front of me here. Today it’s my lucky number.”

I blushed awkwardly at Paul’s description of me. Christine evidently noticed as she shot me a sympathetic smile before negotiating the dizzy heights of her footwear and heading outside. As the door closed behind her, Paul exchanged a mischievous glance with us both.

“She’s fucking gold dust is Christine. She can’t type for toffee, but those knockers are worth fifty grand a year to this business.”

He leaned forward as if he was about to share a state secret. “We had John Fashanu and the Wimbledon boys in here last week. They couldn’t keep their eyes off ‘em. Afterwards, you could hear that flash cunt ‘Awooga’ from the other side of the car park.”

With that, Paul sat back in his chair and abruptly clapped his hands together.

“Right then, Cashy. Let’s get down to business,” he boomed. “How do you feel about Sheffield Wednesday?”

Rich

In 1992, after years of speculation, the elite of English football announced a split from the Football League into the newly-formed Premier League.

Football was emerging from the dark recesses of the Eighties, blighted by hooliganism and crumbling stadia, into a new dawn.

The national team’s success at World Cup 90 had revived interest in the beautiful game. Crowds and viewing figures were on the increase. The Taylor Report, commissioned after the Hillsborough disaster in 1989, assured that the dilapidated structures of old would soon be modernised into all-seater homes for the next generation of football fans.

With a new TV rights deal up for grabs, subscription channel BSkyB sensed opportunity. Rupert Murdoch outbid both the BBC and ITV, inking a staggering £304m five-year deal to secure the prize bounty.

Suddenly blessed with an abundance of riches, top-flight clubs wasted no time in splashing the cash. Champions Leeds added £2m England and Arsenal midfielder David Rocastle to their ranks. Whilst newly-promoted Blackburn Rovers forked out a British record £3.4m for precocious young Southampton striker Alan Shearer and another £1.3m on winger Stuart Ripley from Middlesbrough.

The move to Hillsborough didn’t materialise. Trevor Francis wanted more experience. He suggested I drop down a league for a year and then they might take another look at me.

I thought it sounded perfect. Going to a club with less profile and expectation might be just what I needed. Paul was apoplectic. He was adamant that we should hang on for a top division club. That’s where the money was.

In fact, as of now, that’s where all the money was.

“Listen, Cashy. Football’s rich, son,” said Paul. “It just doesn’t know it yet. You watch. Soon they’ll be paying over the odds for anything they can get their hands on. I just got Ian Holloway a grand a week at QPR. A grand a week! Have you seen him play? If I can get that much for that feisty dollop of shite, I’ll get you five hundred, easy. Stay by the phone, son.”

Breaking a Bond

Despite Paul’s early optimism, over the next few weeks the phone calls dried up.

Billy Bonds got in touch with me about coming back to West Ham. Though they weren’t in the Premier League, it was familiar territory at least. Despite his reputation as a hard man, Billy was a genuinely good guy. At the time of Simon’s accident he’d been youth team coach and it was an open secret that he was being groomed to replace long-serving boss John Lyall.

Billy had been the first to offer me a comforting arm when I returned to training after it became clear there’d be no immediate change to Simon’s condition. We spoke after every session and even if I’d had a stinker, he’d be sure to praise me for doing even the slightest thing right. It helped rebuild my belief and - with Dad distracted by his bedside vigil for Simon - I rediscovered the form that had attracted the attention from Upton Park in the first place. I felt empty playing without my brother, but I couldn’t deny I was playing well. That, combined with my physical gifts, made me an attractive proposition for the scouts once again.

It was Billy who sounded the alarm in 1989 when news of Manchester United’s interest became public. I overheard him tell Dad that I’d be better off staying put, given everything I’d been through. West Ham was a family club that could help nurture me at my own pace. If I went to United, I’d be subject to different expectations.

Dad disagreed. And any loyalty he had to claret and blue had been shoved to the wayside since the accident. There was no time to waste anymore. I had to progress. And there was no better place to progress than England’s most famous club. I was good enough to deal with the expectation, he said.

In the three years that had passed, John Lyall had been sacked and replaced by Stoke’s Lou Macari, who resigned after a matter of months following a betting controversy. The club had turned to Billy, a West Ham legend, to steady the ship. He’d devoted twenty years of his life to the Boleyn Ground. The crowd loved him and if I signed for him, I knew he’d fight my corner if things started going wrong.

I floated it with Paul and he dismissed it out of hand.

By late July, I was secretly starting to look at other options. I was excited by potentially going back into study and either doing more A-levels, this time without football looming in the background, or a college course. I wanted to head back down south, as far away from Dad’s controlling influence as I could get.

I made some phone calls to different schools and colleges. The admissions lady at Oakwood Park would welcome me back with open arms, if I was happy to be in a classroom with immature sixteen year-olds. I said that wouldn’t be a problem. After the dressing rooms at both West Ham and United, where pretty much everyone had given up on school at thirteen, the bar for maturity was set pretty low.

I liked the thought of going back to familiar territory. The school had a private, gated five-a-side pitch – the envy of most schools in the area - which they had kindly named after Simon following the accident. They’d also hung his number eight shirt, which he’d insisted on wearing to emulate Frank McAvennie, in a display case in the main assembly hall, along with a plaque commemorating his sporting achievements. I’d always been grateful for the way they’d honoured his contribution.

That night I went to sleep feeling more positive than I had done in years.

It didn’t last long.

Cloud Cuckoo Land

Paul called at 8am the following morning.

“Do you like yellow, Cashy?” he said. “Good. Because I just got off the phone to Mike Walker at Norwich. He likes the sound of you. The deal’s on.”

The following day we went into Paul’s office to talk through the offer. Dad questioned whether we should hold out for something better. Compared to a club with the rich history of Manchester United, Norwich was something of a fall from grace in his eyes. Paul convinced him that at this stage of pre-season, getting any kind of Premier League club to take a punt on me was quite the coup on his part.

It became clear that one of the big reasons Mike Walker liked me was because I was cheap. His chairman Robert Chase was notoriously tight with the pursestrings and Walker needed bodies in to bolster his threadbare squad before the start of the new season.

“You start at two fifty a week plus bonuses,” said Paul. “Mind you, Norwich have to win the World Cup before you see any of those. He’s a slippery bastard that Chase. Shrewd though, I’ll give him that. Imagine negotiating with Hitler. Except this time he commits mass genocide then tries to fiddle the gas bill.”

(Image: PA Images)

Part of me was relieved. On these wages, having just turned nineteen years of age, it was likely that I’d arrive at Carrow Road with little fanfare. Hopefully I could stay quietly in the background and buy myself some time.

Details agreed, Paul faxed the signed document triumphantly before booming out instructions to his statuesque secretary.

“Christine – get whatever shit rag Norwich calls a local paper on the phone. Tell them that Manchester United star Ray Cash has just signed a big money deal. He’s fit, he’s raring to go and he’s proud to be a Cockatoo.”

“Canary,” I said.

“Eh?”

“Norwich City. They’re called the Canaries.”

“Canaries or Cockatoos. Who fucking cares?” he said. “They’re in the Premier League, Cashy lad, and so are you. Welcome to the big time.”

About the author: Sid Lambert is a football writer who has recently released his highly-acclaimed book Cashing In. It tells the story of Ray Cash, a 19-year-old footballer making his way through the murky world of the Premier League back in 1992, when football changed forever. You can buy it here.

The way to sign with Francisco

“HERE HE IS. ENGLAND’S NEW NUMBER SEVEN!!!”

The hoarse northern voice bellowed across the empty parking lot. We were on a miserable industrial estate fifteen minutes outside of Manchester. In front of us stood a decrepit red brick building that could have passed for an old laundry house were it not for the gawdy neon sign above the door:

FFS: FRANCISCO’S FOOTBALL STARS

“Come on in, son. We’ve been waiting for you.”

Paul Francisco strode towards us. He was six feet tall, weighing in at roughly eighteen stone and built like a rugby prop. In fact, with his slicked-back brown hair and imposing moustache he could have passed as Bill Beaumont’s stunt double, were it not for his extraordinarily bronze skin and equally impressive jewellery collection. Every finger was adorned with gold whilst a watch the size of a medieval sundial nestled cosily on his ample left wrist.

His huge paws swallowed mine as we exchanged a sweaty handshake.

“Great to meet you, Cashy,” he said. “My brother’s told me all about you. Don’t you worry, son. You’re in safe hands here.”

Paul shook hands hurriedly with Dad, who looked dumbfounded by the sight before him. This wasn’t quite the picture either of us had imagined. Undeterred, Paul ushered us into his place of work.

“You’re a lot taller than I thought you were. That’s good. Managers like a bit of height – useful at set pieces,” he winked. “Fuck me, you’re a skinny bastard though. I don’t know whether to open the door or post you through the letterbox.”

He roared with laughter and motioned Dad and I inside.

“Welcome to Francisco’s Football Stars,” he said. “You reach for the stars and I’ll drag ‘em down for you. That’s the way we do things here.”

Awooga

If the outside looked unremarkable, there was at least plenty to remember about the interior of Paul’s office. The door led into a compact space with an empty reception desk and a cheap sofa and coffee table outside the door to what was obviously Paul’s private office. Huge framed pictures of footballers past and present graced every wall, each image suitably defaced with a hasty scrawl from the star in question.

“Look at those names eh, Cashy,” he said. “Brian Kilcline, John Sheridan, Brian Deane, Ian Crook, Rod Wallace. First Division royalty that lot.

You’ll be up there too, son. Don’t you worry.”

He patted me on the shoulder and I nearly crumpled under the force.

“And here’s my pride and joy…”

He pointed over to the wall behind us near the door, where the whole surface area was occupied by a life-size picture of Paul and Newcastle United striker Micky Quinn. Both men were clutching a hot dog and a can of lager against the backdrop of an overcast racecourse.

“What a day that was. Me and Quinny celebrating his new contract,” he said. “We’ve got him down to 10% body fat, you know. It’s the 90% Heineken that’s the fucking problem.”

His hearty laugh nearly shook the foundations of the building and it continued as he led us into his private office. Unlike the rest of the building it was an immaculate space and free from football paraphernalia. The desk looked like it was made of solid oak and regularly varnished. It was adorned with a lamp, a phone and a clumsy assortment of files strewn across the remaining surface area – the epitome of organised chaos.

(Image: ITV/Rex Shutterstock)

The walls were a faint beige, contrasting with the warm red carpet, and behind Paul’s desk was an image I recognised from my history textbooks at school. It was from World War Two, depicting the view from inside one of the warships as the troops unloaded onto the French beaches into a barrage of German machine gun fire. On the bookshelves to the right, there were numerous tomes on war and a couple of Winston Churchill biographies.

Aside from two dark grey filing cabinets, that was the sum total of decoration, except for one curiosity in the corner of the room. There stood a large shoe rack, immaculately maintained in stark contrast to the anarchy of the desk space. It held maybe twenty pairs of shoes, mainly black and deep browns. They were all in pristine condition. Next to the shoe rack was an array of materials – buffers, brushes and polish - charged with keeping them that way.

Paul shouted out to his secretary to bring in refreshments. She tottered in immediately, struggling to remain upright. At first I thought it might be the shoes that were causing her unbalance but as my eyes drifted upwards I could see that in fact it was the astonishing size of her chest, barely sustained by her implausibly small vest top.

“Teas all round?” she asked.

Dad and I nodded, both awestruck by the freak of nature before our eyes. With long blonde hair big blue eyes, and make-up that most Page Three girls would be proud of, it was tempting to assume that the recruitment policy for secretaries at Francisco’s Football Stars might not be based on words per minute.

“How many sugars do you want today, Paul? Five or six?” she asked.

“Fuck it. Let’s go for seven eh, Christine. I’ve got England’s next right winger in front of me here. Today it’s my lucky number.”

I blushed awkwardly at Paul’s description of me. Christine evidently noticed as she shot me a sympathetic smile before negotiating the dizzy heights of her footwear and heading outside. As the door closed behind her, Paul exchanged a mischievous glance with us both.

“She’s fucking gold dust is Christine. She can’t type for toffee, but those knockers are worth fifty grand a year to this business.”

He leaned forward as if he was about to share a state secret. “We had John Fashanu and the Wimbledon boys in here last week. They couldn’t keep their eyes off ‘em. Afterwards, you could hear that flash cunt ‘Awooga’ from the other side of the car park.”

With that, Paul sat back in his chair and abruptly clapped his hands together.

“Right then, Cashy. Let’s get down to business,” he boomed. “How do you feel about Sheffield Wednesday?”

Rich

In 1992, after years of speculation, the elite of English football announced a split from the Football League into the newly-formed Premier League.

Football was emerging from the dark recesses of the Eighties, blighted by hooliganism and crumbling stadia, into a new dawn.

The national team’s success at World Cup 90 had revived interest in the beautiful game. Crowds and viewing figures were on the increase. The Taylor Report, commissioned after the Hillsborough disaster in 1989, assured that the dilapidated structures of old would soon be modernised into all-seater homes for the next generation of football fans.

With a new TV rights deal up for grabs, subscription channel BSkyB sensed opportunity. Rupert Murdoch outbid both the BBC and ITV, inking a staggering £304m five-year deal to secure the prize bounty.

Suddenly blessed with an abundance of riches, top-flight clubs wasted no time in splashing the cash. Champions Leeds added £2m England and Arsenal midfielder David Rocastle to their ranks. Whilst newly-promoted Blackburn Rovers forked out a British record £3.4m for precocious young Southampton striker Alan Shearer and another £1.3m on winger Stuart Ripley from Middlesbrough.

The move to Hillsborough didn’t materialise. Trevor Francis wanted more experience. He suggested I drop down a league for a year and then they might take another look at me.

I thought it sounded perfect. Going to a club with less profile and expectation might be just what I needed. Paul was apoplectic. He was adamant that we should hang on for a top division club. That’s where the money was.

In fact, as of now, that’s where all the money was.

“Listen, Cashy. Football’s rich, son,” said Paul. “It just doesn’t know it yet. You watch. Soon they’ll be paying over the odds for anything they can get their hands on. I just got Ian Holloway a grand a week at QPR. A grand a week! Have you seen him play? If I can get that much for that feisty dollop of shite, I’ll get you five hundred, easy. Stay by the phone, son.”

Breaking a Bond

Despite Paul’s early optimism, over the next few weeks the phone calls dried up.

Billy Bonds got in touch with me about coming back to West Ham. Though they weren’t in the Premier League, it was familiar territory at least. Despite his reputation as a hard man, Billy was a genuinely good guy. At the time of Simon’s accident he’d been youth team coach and it was an open secret that he was being groomed to replace long-serving boss John Lyall.

Billy had been the first to offer me a comforting arm when I returned to training after it became clear there’d be no immediate change to Simon’s condition. We spoke after every session and even if I’d had a stinker, he’d be sure to praise me for doing even the slightest thing right. It helped rebuild my belief and - with Dad distracted by his bedside vigil for Simon - I rediscovered the form that had attracted the attention from Upton Park in the first place. I felt empty playing without my brother, but I couldn’t deny I was playing well. That, combined with my physical gifts, made me an attractive proposition for the scouts once again.

It was Billy who sounded the alarm in 1989 when news of Manchester United’s interest became public. I overheard him tell Dad that I’d be better off staying put, given everything I’d been through. West Ham was a family club that could help nurture me at my own pace. If I went to United, I’d be subject to different expectations.

Dad disagreed. And any loyalty he had to claret and blue had been shoved to the wayside since the accident. There was no time to waste anymore. I had to progress. And there was no better place to progress than England’s most famous club. I was good enough to deal with the expectation, he said.

In the three years that had passed, John Lyall had been sacked and replaced by Stoke’s Lou Macari, who resigned after a matter of months following a betting controversy. The club had turned to Billy, a West Ham legend, to steady the ship. He’d devoted twenty years of his life to the Boleyn Ground. The crowd loved him and if I signed for him, I knew he’d fight my corner if things started going wrong.

I floated it with Paul and he dismissed it out of hand.

By late July, I was secretly starting to look at other options. I was excited by potentially going back into study and either doing more A-levels, this time without football looming in the background, or a college course. I wanted to head back down south, as far away from Dad’s controlling influence as I could get.

I made some phone calls to different schools and colleges. The admissions lady at Oakwood Park would welcome me back with open arms, if I was happy to be in a classroom with immature sixteen year-olds. I said that wouldn’t be a problem. After the dressing rooms at both West Ham and United, where pretty much everyone had given up on school at thirteen, the bar for maturity was set pretty low.

I liked the thought of going back to familiar territory. The school had a private, gated five-a-side pitch – the envy of most schools in the area - which they had kindly named after Simon following the accident. They’d also hung his number eight shirt, which he’d insisted on wearing to emulate Frank McAvennie, in a display case in the main assembly hall, along with a plaque commemorating his sporting achievements. I’d always been grateful for the way they’d honoured his contribution.

That night I went to sleep feeling more positive than I had done in years.

It didn’t last long.

Cloud Cuckoo Land

Paul called at 8am the following morning.

“Do you like yellow, Cashy?” he said. “Good. Because I just got off the phone to Mike Walker at Norwich. He likes the sound of you. The deal’s on.”

The following day we went into Paul’s office to talk through the offer. Dad questioned whether we should hold out for something better. Compared to a club with the rich history of Manchester United, Norwich was something of a fall from grace in his eyes. Paul convinced him that at this stage of pre-season, getting any kind of Premier League club to take a punt on me was quite the coup on his part.

It became clear that one of the big reasons Mike Walker liked me was because I was cheap. His chairman Robert Chase was notoriously tight with the pursestrings and Walker needed bodies in to bolster his threadbare squad before the start of the new season.

“You start at two fifty a week plus bonuses,” said Paul. “Mind you, Norwich have to win the World Cup before you see any of those. He’s a slippery bastard that Chase. Shrewd though, I’ll give him that. Imagine negotiating with Hitler. Except this time he commits mass genocide then tries to fiddle the gas bill.”

(Image: PA Images)

Part of me was relieved. On these wages, having just turned nineteen years of age, it was likely that I’d arrive at Carrow Road with little fanfare. Hopefully I could stay quietly in the background and buy myself some time.

Details agreed, Paul faxed the signed document triumphantly before booming out instructions to his statuesque secretary.

“Christine – get whatever shit rag Norwich calls a local paper on the phone. Tell them that Manchester United star Ray Cash has just signed a big money deal. He’s fit, he’s raring to go and he’s proud to be a Cockatoo.”

“Canary,” I said.

“Eh?”

“Norwich City. They’re called the Canaries.”

“Canaries or Cockatoos. Who fucking cares?” he said. “They’re in the Premier League, Cashy lad, and so are you. Welcome to the big time.”

About the author: Sid Lambert is a football writer who has recently released his highly-acclaimed book Cashing In. It tells the story of Ray Cash, a 19-year-old footballer making his way through the murky world of the Premier League back in 1992, when football changed forever. You can buy it here.